How to use the attacks repository

Each row in this repository corresponds to a research paper that describes an output privacy attack. Before diving into the column definitions, it is helpful to begin with a concrete example.

Example Entry

| Title | Authors | Year | Data Type (Inputs) | Type of Data Release (Outputs) | Attacker Objectives | Research Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The 2010 Census Confidentiality Protections Failed, Here's How and Why |

John M. Abowd et al.John M. Abowd, Tamara Adams, Robert Ashmead, David Darais, Sourya Dey, Simson L. Garfinkel, Nathan Goldschlag, Daniel Kifer, Philip Leclerc, Ethan Lew, Scott Moore, Rolando A. Rodríguez, Ramy N. Tadros, Lars Vilhuber |

2023 | Tabular | Linear Queries | Reconstruction | Empirical |

This example illustrates how each paper is cataloged according to the data type, release type, attacker objective, and other metadata that enable cross-comparison and filtering across the literature. You can use the repository’s built-in search and filter tools to quickly locate papers relevant to your interests.

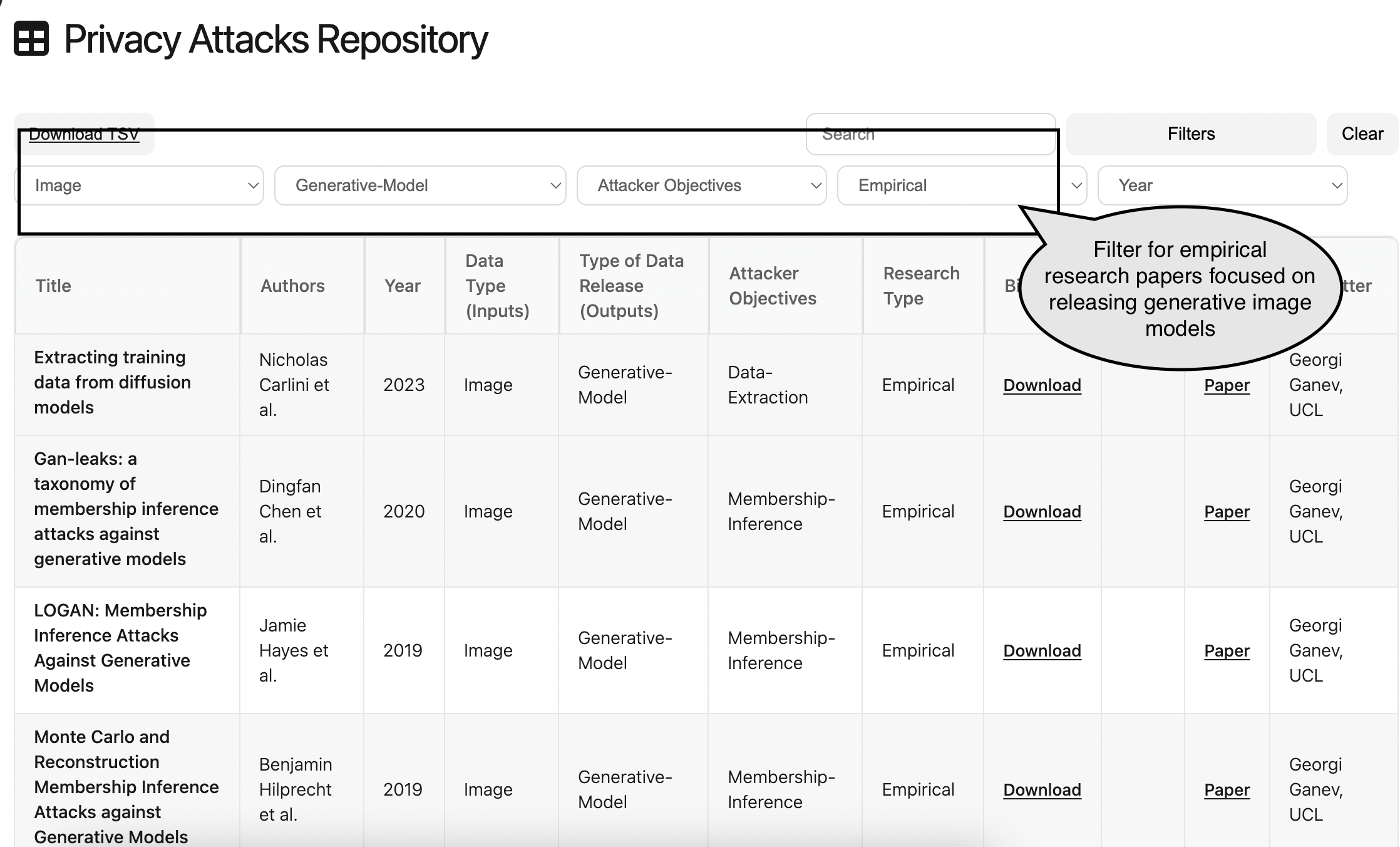

For example, to find empirical attacks on generative image models, you might:

- Filter Data Type (Inputs) to

Image. - Filter Type of Data Release (Outputs) to

Generative Models. - Filter Research Type to

Empirical.

The figure below shows an example of applying these filters to obtain a focused subset of the literature.

Repository Structure

The information associated with each paper in the repository follows the format:

- A. URL

- B. BibTeX entry

- C. Authors

- D. Title

- E. Short description

- F. Type of data (inputs)

- G. Type of data release (outputs)

- H. Threat model — attacker objectives

- I. Threat model — attacker capabilities

- J. Research type

- K. Link to artifacts

- L. Additional comments

- M. Submitter information

Columns A–D and J–M we believe are fairly standard. Columns F–I are more structured and rely on specialized terminology associated with the research on privacy attacks. For users who are just getting started with this literature, we will give a quick introduction to the terminology and links to resources for further reading.

Type of Data. Describes the type(s) of input data considered in the paper. The most common types are

-

Tabular. Data laid out in a traditional table with one axis (typically rows) representing different data points and another axis (typically columns) representing different features. In these datasets we often think of each individual person’s data as corresponding to a single row of the table.

-

Image. Data composed of pixels arranged in a 2D (or 3D for color images) grid. Each image is typically represented by numerical pixel intensity values across channels (e.g., RGB).

-

Text. Data composed of sequences of characters or tokens (e.g., words, subwords). Typically represented numerically using embeddings or tokenized integers.

-

Type of Data Release. Describes the type(s) of output(s) that are produced from the dataset.

-

Counts and Linear Queries. A count query has the form “How many elements of this dataset are voting-age, hispanic, males living in Massachusetts?” In the literature these are often called linear queries for technical reasons. These queries are most commonly associated with tabular datasets and applications such as the US Decennial Census, but are well defined for other types of data.

- Predictive Model. Predictive models map input features to target outputs and are trained on labeled data. They are typically used to predict unknown or future values based on historical data. Examples include:

- Simple Predictive Models (e.g., Linear or Logistic Regression):

- Neural Networks (e.g., Deep Learning Models):

- Simple Predictive Models (e.g., Linear or Logistic Regression):

- Generative Models. Produce new synthetic data points (e.g., text, images, audio) that resemble the training data distribution. LLMs (e.g., GPT), diffusion models for images (e.g., Stable Diffusion), and generative adversarial networks (GANs) are typical examples.

Threat Model -– Attacker Objectives. Describes what constitutes “success” for the attacker, typically by specifying some piece of information that is unknown to the attacker and a criteria for recovering that information sufficiently well. While there are some variations in how each attacker objective is defined, and sometimes different threat models can blur together at the boundaries, we can describe the basic categories of threat model.

Data Reconstruction. As its name suggests, a reconstruction attack is a method for an attacker to use a data release to reconstruct all or part of a dataset. Typically the attacker also has access to some partial knowledge of the dataset itself, of the distribution that generated the data. For example, we might model the dataset as consisting of some publicly known identifiers that the attacker already has (e.g. birthdate, sex, race, and zipcode for each individual) and some secret information (e.g. citizenship status), and we release various pieces of demographic information about this dataset (e.g. statistics about the proportion of non-citizens across different demographics and regions) the attacker combines the publicly known identifiers with some released statistics to reconstruct the secret information for all or most people. These attacks have been most commonly seen in tabular data releases, but have also been applied to large neural networks. We suggest the following blog posts from differentialprivacy.org for some history of reconstruction attacks and overviews of reconstruction attacks in theory and in practice.

Membership Inference. In a membership inference attack, the attacker is given the data release, and all of the data belonging to a specific individual, and tries to determine if that individual’s data was or was not used to produce the data release. Typically the attacker also has access to some knowledge of the distribution that was used to generate the data. The original example of membership inference comes from genomic data where an attacker had access to genetic information about a large set of individuals, and statistical information about the subset of individuals who suffered from a particular disease, and was able to infer whether a specific individual did or did not suffer from the disease. This example also shows how membership in the dataset can be a privacy violation, even if the attacker already has a large amount of information about a specific individual. Membership-inference can also be a building block for reconstruction attacks, and in general offers a flexible framework for describing what kinds of privacy violations we might see against an informed attacker. Although they were originally studied for simple tabular datasets, membership-inference attacks have been most widely studied for large neural networks and generative models, and are the standard methods for studying output privacy for these types of releases. We suggest the following survey for more background on membership-inference (and other attacks).

Data Extraction. In a data extraction attack, which is most commonly seen in large generative models (e.g. LLMs), the attacker uses the data release to contain a long, unique piece of training data belonging to an individual. For example, an attacker can prompt language models to release specific identifying information such as the name of a person, their birthdate, and their home address when that information was used in the training of the model. See this paper for the first example of deploying these attacks on production language models, and some discussion of issues in modeling and measuring data extraction.

Attribute Inference. In an attribute inference attack, the attacker uses the data release to infer global properties of sensitive attributes in the dataset. As described in this paper introducing attribute privacy, these global properties pertain to the dataset itself or the underlying distribution from which the dataset is sampled, rather than to individuals in the dataset. In the first case, for example, a hospital may wish to protect the incidence of a disease in its patients,, even if the prevalence of that disease in the broader population is public information. In the second case, a pharmaceutical company may want to protect its experimental findings about the effect of a new drug on the population. However, other papers consider individual-level attribute inferences, separating sensitive from non-sensitive attributes. This paper provides a nice overview of different definitions related to attribute inference.

Threat Model -– Attacker Capabilities. This column describes the particular capabilities that we assume the attacker needs to run the attack successfully. These capabilities often take the form of some kind of background knowledge about any or all of (1) the distribution the data was drawn from as well as the specific dataset, and (2) the particulars of the algorithm releasing the release and how the attacker can interact with that release. Some examples include issuing adaptive queries to the privacy mechanism, or inserting poisoned examples to the training data. This information is much less structured, and often the ways research papers differ in attacker capabilities is highly specific to the data type, release type, and attacker objective. As a result, we left the column free-text.